Prof. Janek Ratnatunga

Introduction

Consumers increasingly expect brands to have not just functional benefits but also a social purpose. Brands increasingly use a social purpose to guide marketing communications, inform product innovation, and steer investments toward social cause programs.

Here in Australia, “Who Gives A Crap”, an online toilet paper manufacturer and marketer, donates half its profits to charities. With a slogan ‘Profits for Purpose’, the company finances projects that build toilets in schools in lower-income countries. Often a lack of proper toilets means a lack of schooling, especially for girls. WGAC’s charity donations in 2021 were the highest in Australia, beating both Qantas and Coca-Cola.[i]

All this is very noble; but how does it stack up against the traditional measure of corporate performance, i.e., Return on Investment (ROI)?

Whilst WGAC had a social purpose from its inception, more established companies are realising that being seen as socially and environmentally conscious can boost profitability as it draws new customers that otherwise may not have been interested in its products or services. For example, Tecate, based in Mexico, is investing heavily in programs to reduce violence against women, and Vicks, a P&G brand in India, supports child-adoption rights for transgender people. Both these social purpose initiatives have positively impacted market share and profitability.

For the management accountant there are resource allocation concerns when considering ‘social purpose’ in an organisation’s integrated marketing communication (IMC) budgets. Today, it is even more important to be able to stretch the limited resources allocated for marketing communication in the most appropriate way. Social purpose strategies dictate that advertising and promotion should be used not only to create, communicate, and deliver value in order to influence target audience behaviours – but there should also be the added dimension that such behaviour should benefit society.

This then is the new holy-grail of the marketing–finance interface. Let us look at marketing first, and then finance.

Social Purpose Marketing

Social Purpose Marketing (SPM) is an approach used to develop activities aimed at changing or maintaining people’s behaviour for the benefit of both the individual and the society. The five main components of SPM are: (1) that it focuses on behaviour change (2) that is voluntary (3) using marketing principles and techniques (4) to select and influence a target audience (5) for their benefit.[ii]

Such a marketing approach stems from the lens of social responsibility in marketing. This involves focusing efforts on attracting consumers who want to make a positive difference with their purchases. Many companies have adopted socially responsible elements in their marketing strategies to help a community via beneficial services and products.

Increasingly, social marketing is described as having “two parents.” The “social parent” uses social science and social policy approaches. The “marketing parent” uses commercial and public sector marketing approaches.[iii] Recent years have also witnessed a broader focus. Social marketing now goes beyond influencing individual behaviour. It promotes socio-cultural and structural change relevant to social issues.[iv]

Combining ideas from commercial marketing and the social sciences, SPM is a proven tool for influencing behaviour in a sustainable and cost-effective way. A company’s SPM strategy needs to focus on: (a) which people to work with; (b) what behaviour to influence; (c) how to go about it; and importantly (d) how to evaluate its impact.

The goal of SPM is to actually change or maintain how people behave – not just what they think, or how aware they are, about an issue. If an organisation’s goal is only to increase awareness or knowledge of their product or service, or only change attitudes rather than behaviour – then it is not doing social purpose marketing. Therefore, it is not what is assumed by the company to benefit those targeted by its social marketing intervention but instead the value – perceived or actual – of the behaviour changes (actions) brought about by the intervention.

Thus, knowing that tobacco causes cancer, or that plastic bottles are polluting oceans, or that cattle produce the most greenhouse gas emissions – is not enough. The social marketing intervention must result in behaviour changes of those targeted to stop smoking, use glass bottles or reduce their beef intake.

This attitude vs behaviour dichotomy is similar to commercial sector marketers who focus on people buying their goods and services – they understand that just the awareness of a product or service is not sufficient to make a sale. In SPM, change agents typically want target audiences to do one of four things: (a) accept a new behaviour (e.g., recycling), (b) reject a potential behaviour (e.g., not starting smoking), (c) modify a current behaviour (e.g., increase physical activity from 3 to 5 days of the week), or (d) abandon an old behaviour (e.g., do not drink liquor alone). Although the primary beneficiary of the social marketing program is the’ individual’ – through his or her improved health and quality of life – collectively this leads to society benefiting from a healthier and more productive population.

The behaviour change brought about by SPM strategies are typically voluntary — i.e., the core of the approach is to achieve a level of understanding and empathy of the audience for them to self-discover motivations and personal benefits. This will enable the targeted audience to link their changing behaviours to a company’s product or service offerings.

Thus, the most fundamental principle underlying SPM is to apply a consumer orientation to designing the product (or service) — i.e., understand what target audiences currently know, believe, and do. Then, the product is positioned to appeal to the motivations of the target market to improve their health, prevent injuries, protect the environment, or contribute to their community more effectively than the competing behaviour the target market currently practices or is considering.[v]

Despite these lofty purposes, countless well-intentioned social-purpose programs have consumed resources and management time only to end up in obscurity. Sometimes they backfire because the brand messages designed to promote these programs may anger or offend customers — or they simply go unnoticed because they fail to resonate. Other times, managers use these initiatives solely to pursue intangible benefits such as brand affection or to communicate the company’s corporate social responsibility, without consideration of how they might create business value for the firm.[vi]

This is where social purpose marketing programs need to integrate with social purpose finance objectives, which we will discuss next.

Social Purpose Finance

Social Purpose Finance (SPF) is an approach to managing investments that generate financial returns whilst having a measurable positive social and environmental impact. Money is provided by investors who want to see it giving a return and, simultaneously, see that it has been spent on making society better. SPF is a category of financial services which aims to leverage private capital to address challenges in areas of social and environmental need; and thus, provide finance to build an organisation’s long-term capacity to achieve its social mission.

Traditionally, investors have evaluated firm performance based on financial measures alone. But investing with an eye to environmental or social issues, not just financial returns, has become mainstream in the past decade. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), a global umbrella group, a total of $35.3trn, or 36% of all assets under management in 2020, were in ‘socially responsible investments’ that take account of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues.[vii]

Note that the difference between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and ESG is that while CSR impacts internal processes and company culture, ESG is a measurable set of propositions that external partners and investors look at in their evaluation of a company. ESG illustrates a company’s identification and quantification of its risks and opportunities, as well as highlights the ethics of a company.[viii]

Having gained popularity in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, SPF is notable for its public benefit focus.[ix] Mechanisms of creating shared social value are not new, however, social finance is conceptually unique as an approach to solving social problems while simultaneously creating economic value.[x] Unlike philanthropy, which has a similar mission-motive, social finance secures its own sustainability by being profitable for investors.[xi] Capital providers lend to social enterprises who in turn, by investing borrowed funds in socially beneficial initiatives, deliver investors measurable social returns in addition to traditional financial returns on their investment.[xii]

Take the impact of Covid-19 which had a significant impact in major investments in pharmaceuticals (e.g., vaccines) and the health-care system (e.g., emergency facilities at hospitals). Some companies such as AstraZeneca decided to provide its vaccine at no profit whilst Covid-19 was a pandemic; announcing that its top priority was to protect global health.[xiii] Others, like Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna made significant profits from day one of their respective vaccine releases (more on this later).

Like SPM, the goal of SPF is to finance projects that actually change or maintain people’s behaviour, rather than their attitudes. However, there is the added dimension of a positive return on investment (ROI). Thus, SPF includes a full range of investment strategies and solutions across asset classes that can provide an array of risk-adjusted returns tailored to investor behaviour that benefits society.

Thus, knowing that mining fossil fuels contributes to global warming is not enough if investor behaviour continues to support such industries (by purchasing petrol and diesel vehicles). What is needed is investor behaviour (actions) that support renewable energy production and consumption (e.g., installing solar panels and driving electric cars).

Other socially responsible investments include eschewing investments in companies that produce or sell addictive substances or activities (like alcohol, gambling, and tobacco) in favour of seeking out companies that are engaged in social justice, environmental sustainability, and alternative energy/clean technology efforts. [See Appendix One on four key social purpose finance strategies].

SPF investors who want to have a positive impact on society are developing a growing awareness that they are no longer limited to doing so through donations to charitable and other non-profit organisations. SPF offers ways for investors to extend their influence by aligning their goals for public good and positive impact with their desire for wealth accumulation and legacy gifting.

Decisions to explore or adopt social finance strategies are not necessarily driven by charitable intent, nor do those decisions always stem from a desire to earn attractive investment returns. These decisions are often based on the following motivations:

Personal Values: For some individuals, deciding to invest in a socially responsible manner stems from strongly held personal beliefs. Their primary focus is to avoid advancing the interests of organisations or industries that go against those beliefs. For example, in Australia, investments in companies that mine fossil fuels are being avoided by many due to climate change issues.

Fiduciary Obligations: As part of their risk management strategies and fiduciary obligations, trustees for non-profit organisations, superannuation (pension) funds or others investing in a fiduciary capacity may search for investments that have competitive investment returns whilst meeting ESG criteria.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Goals: Some SPF investors want to incorporate values-based investing with altruistic intent, seeking competitive returns from investments which also focus on ESG opportunities. One such example is a mutual fund that invests in emerging markets infrastructure or in clean-energy initiatives.

Connection to the Next Generation: SPF strategies allow investors and their families to clearly identify shared values and goals and align them across areas of mutual interest. Because younger generations may want to put a greater focus on sustainable investing to achieve social and environmental impact, social finance is also a great way to bridge the gap between generations.

Sustainable vs. Normal Investments

The area of SPF suffers from definitional quibbles over where to draw the line between sustainable and “normal” investments; and how to subdivide the universe of sustainable investment. Thus, SPF strategies require an understanding of the role of Environmental & Social Governance (ESG) factors in managing investor risk to create innovative blended finance and pay-for-performance approaches that steer new investments into target markets that benefit society.

Many companies (and consultants in the area) have encompassed many diverse areas under the SPF universe, such as: (a) innovative finance; (b) domestic resource mobilisation strategies; (c) socially responsible investing; (d) social impact bonds (SIBs) (e) pay-for-performance; (f) impact Investing; (g) blended finance; and (h) alternative financing vehicles for non-profits.

The GSIA, for instance, counts seven distinct strategies. (1) Negative/exclusionary screening; (2) Positive/best-in-class screening; (3) Norms-based screening, (4) ESG integration; (5) Sustainability themed investing; (6) Impact/community investing, and (7) Corporate engagement and shareholder action.[xiv]

GSIA stated that the most common sustainable investment strategy is ESG integration, followed by negative screening, corporate engagement and shareholder action, norms-based screening, and sustainability-themed investment. ‘ESG integration’, the largest strategy by the GSIA’s reckoning, involves taking ESG factors into account in the investment process (though the way investment firms do this in practice varies widely). ‘Negative screening’, simply excludes assets deemed unsavoury. An example would be a stock portfolio that otherwise tracks a broad index but excludes the shares of tobacco companies or gunmakers.

Of the remaining strategies, perhaps the most interesting is ‘impact investment’, which has received a lot of attention recently. Although it is the smallest by total assets, it is also by far the most ambitious. Impact investors only invest in projects or firms where the precise impact can be quantified and measured: for instance, the reduction in tonnes of carbon dioxide emitted by a firm’s factory, or the number of girls educated in a village school as a result of a particular project. These variants are quite different, but most are set up on the premise that financial return need not be sacrificed in pursuit of non-financial goals.[xv]

The Holy Grail: Integrated Social Purpose Strategies

What is needed, therefore, is an integrated marketing-finance strategy that ties a company’s most ambitious social aspirations to its most pressing growth needs.

Some brands have had an integrated social purpose (i.e., integrating both SPM and SPF) built into their business models right from the start. The societal benefit that these ’social purpose inbreds’ offer is so deeply entwined with their product or service that it is hard to see these brands’ surviving intact without it. Imagine what would happen to the ‘Who Gives a Crap’ brand if the company abandoned its commitment to both eco-friendly manufacturing and its commitment to donate half its profits to charity? Thus, those with a pedigree in social purpose activities like WGAC must be diligent stewards of their brands and social-purpose strategy from inception.

The challenges are very different for the much larger number of brands that are ‘social-purpose adopters’ — they have grown without a well-defined social-purpose strategy and are now seeking to develop one. Typically, they belong to firms that are good corporate citizens and are committed to progress on environmental and social goals. However, their growth has thus far been based on superior functional performance that is unrelated to a broader social purpose.[xvi]

Although few brands are likely to start with a blank slate — today most have CSR programs underway — some projects could become relevant to the brand’s social purpose value proposition in the future. Yet focusing only on CSR initiatives could limit the potential of a purpose-driven brand strategy or divert marketing resources meant to stimulate the brand’s growth toward other corporate initiatives such as profit growth. To create a more comprehensive and integrated set of choices, managers should explore social purpose ideas in three domains: (1) Brand Heritage; (2) Customer Tensions; and (3) Product Externalities.

Brand Heritage: A brand’s ‘heritage’ is the most salient benefit the brand offers customers. Closely examining this can help managers identify the social needs that their brands are well positioned to address. For example, Dove has been promoted as a beauty bar, not a soap — enhancing beauty has always been central to its value proposition. Studies have shown that ‘Beauty’ is intimately correlated with both physical and mental health — and that in most societies, at all ages and in all walks of life, attractive people are judged more favourably, treated better, and get more leeway.[xvii] Therefore, it makes sense that Dove focuses on social needs tied to perceptions of beauty, and this has made it a profitable brand as well.

Customer Tensions: Instead of taking a wide exploration of relevant social issues, companies should take a very narrow look at the “cultural tensions” that affect its customers and which can be related to its brand heritage. Such tensions are the conflict people often feel when their own experience conflicts with society’s prevailing ideology. Brands can become more relevant by addressing consumers’ desire to resolve these tensions. Classic examples include Coca-Cola’s “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” commercial, which promoted peace and unity at the height of the Vietnam War; and its more recent ‘Arctic Home’ program, a partnership launched in 2011 with the World Wildlife Fund to protect polar bears from the impact of global warming.

Product Externalities: Companies also need to examine the impact of their products or services in terms of ‘externalities’ — i.e., the indirect costs borne (or benefits gained) by a third party as a result of its manufacture or use. For instance, the food and beverage industry has been criticised for the contribution of some of its products to the increasing rates of childhood obesity. It has also faced concerns about negative health effects resulting from companies’ use of artificial ingredients and other chemicals in their products. McDonald’s offering healthy options as part of its popular value meals, and letting customers choose a side salad, fruit, or vegetables instead of French fries — is a direct response to a social need created by industry externalities. Another example was how the chemicals industry was successful in diverting attention away from the plastic pollution pandemic by launching a 3-R (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) campaign that placed a guilt and cost burden on the user rather than the manufacturer.

Competing in Adjacent Markets

It has already been mentioned that a social purpose marketing strategy can fall short of expectations if it does not simultaneously address the financial interests of investors and other stakeholders. Thus, one way an integrated social purpose strategy can boost business performance is by enabling the brand to compete in adjacent markets.

Consider Brita, a German company which until 2005 primarily sold tap-water filters worldwide, including in Australia. Concerned by slowing growth, Brita seized on a social need — waste reduction — to push into the adjacent bottled-water market by positioning filtered water as an environmentally friendly alternative. In its marketing, Brita emphasised the water’s “great taste and purity” and its economic value over time relative to bottled water. But its central message: “300 plastic bottles kept out of landfills and oceans for each Brita filter used”, was the environmental benefit of substituting filtered water for bottled water. Three years after Brita entered this adjacent market, its revenues had grown by 47%.

To gauge whether a proposed brand’s integrated social purpose strategy can support a move into adjacent markets, its managers should ask: (a) can the strategy help create a new product or service for current customers? (b) can it help open a new market or channel or attract a new customer segment? and (c) can it help reduce costs or increase the profitability of the business?[xviii]

Obstacles to an Integrated Social Purpose Strategy

An obstacle to stakeholder acceptance of an integrated social purpose strategy occurs when companies, unwittingly or not, adopt a controversial social purpose. This was the case with Coca-Cola’s ‘Arctic Home’ program referred to earlier. It partnered with the World Wildlife Fund in 2011 to protect polar bears. The social mission fitted well with the brand, which had long used the animal in its advertising. However, even though its leaders never intended to equate a conservation initiative with the politics of climate change, the program catapulted Coke into the middle of a political debate between climate crusaders and climate deniers. Whilst a significant segment of the population regarded global warming as a serious problem, some vocal climate sceptics saw the Coke campaign as a mass media effort to promote a political agenda. While the company succeeded in containing a more general outcry, its experience highlights the risk of politicisation around a brand’s social purpose. It is unlikely that any social-benefit claim can escape criticism, but management’s goal must be to maximise the fan-to-foe ratio.

Further, whilst stakeholders understand that companies are profit-driven; they may question a brand’s motives if the initiative appears to be driven primarily by commercial interests. Stakeholders may feel manipulated if the company’s initiative offers no apparent social benefit — as often happens if a brand is found to be ‘greenwashing’; i.e., using marketing spin or green PR to deceptively persuade the public that an organisation’s products, aims, and policies are environmentally friendly.[xix] To mitigate this risk, it is critical to select a social purpose for which the brand can make a material contribution.

Thus, to assess whether an integrated social purpose strategy is likely to be accepted by stakeholders, managers should ask: (a) can the brand have a demonstrable impact on the social need? (b) are key stakeholders on the front lines of the social issue likely to support the brand actions? and (c) can the brand avoid inconsistent messaging, perception of opportunism, and politicisation?

Define the Brand’s Role

Once a company decides which social need a brand will focus on, managers must determine how the brand strategy will create value for it. Researchers at the Harvard Business School discovered four ways that a brand can create value for a social need. This taxonomy provides a useful tool for thinking about how a brand can best execute on its purpose. It can also guide managers in the selection of metrics for measuring the impact of their social-purpose investments.[xx] The four ways are to:

Generate Resources: Brands can make an impact by helping generate the resources required to address a social need. Most commonly, this involves the donation of financial resources: When consumers buy a product, the brand gives a percentage of the profits to a selected cause. Who Gives a Crap donates 50% of profits for sanitation projects in developing countries globally. Other resources could also include time, talent, relationships, and capabilities.

Provide Choices: Brands can offer consumers products that address a social need and can be substituted for those that do not. Brita filters, for example, gave customers an alternative to bottled water that does not add plastic to landfills.

Influence Mindsets: Brands can help shift perspectives on social issues. Examples include Nike’s communications efforts to promote the participation of girls in sports and its recent campaign to promote racial and gender equality.

Improve conditions: Brand actions can help establish the conditions necessary to address a social need. Consider Coca-Cola’s Ekocenter initiative in Africa. Through a multi-stakeholder partnership, the brand is creating community centres with clean water, solar power, and internet access, among other services. These centres also house modular markets run by local female entrepreneurs.

AstraZeneca vs Pfizer: A Case Study of an Integrated Social Purpose Strategy

The contrast of the profit vs. social purpose approaches of AstraZeneca and Pfizer is a case in point.

Early in the pandemic, when it was approved as a vaccine against Covid-19, AstraZeneca decided to provide millions of doses at no profit, because, according to its chief executive Mr. Pascal Soriot, the company’s top priority was to protect global health. He told the BBC he had “absolutely no regrets” about not making a profit when competitors had been doing so, as it has saved millions of hospitalisations.[xxi]

The evidence is overwhelming that the AstraZeneca vaccine, which was developed with the publicly funded University of Oxford, has saved a million lives around the world — especially in lower-income countries.[xxii] Among the reasons for a preference for AstraZeneca in such countries are considerations around supply, cost, and logistical issues. For example, the vaccine requires only regular refrigerator storage, compared with the mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and others which need to be frozen.

Pfizer, on the other hand, clearly had both a social purpose and a profit motive from the start. Consequently, it sold and distributed billions of doses of its Covid-19 vaccine, generating an estimated $36 billion profit in 2021. However, Pfizer’s super profits has virtually eliminated its social purpose message. When asked about what the company is doing with all these vaccine super-profits, Pfizer’s CEO Mr. Albert Bourla said:

“We are investing in research. Our R&D expenses, in the last three years went from the seven to almost 11 billion dollars per year”.[xxiii]

At face value an increase of 4 billion on R&D does not seem to justify the inordinate mark-up of the Pfizer product. In fact, the cost-price comparisons are staggering. A normal profit margin in the drugs industry is about 20%. Mr Soriot said AstraZeneca charged about US$5 per shot for the Covid vaccine. This was close to cost price, and therefore, the company made a much lower profit margin.[xxiv] In contrast, Pfizer’s profit margin has been estimated at between 70-77%.[xxv]

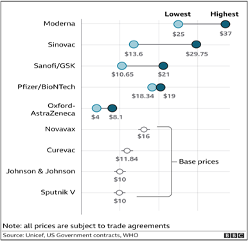

Figure 1: Price per Dose Ranges of Vaccine Makers (in US$)

In fact, AstraZeneca was by far the lowest priced vaccine, selling at a price range between US$4 and $8.10 per dose; whilst Pfizer prices ranged between US$18.34 and $19 (Figure 1). Multiply this by the billions of doses and one can see how the returns pile up.

It is now evident that Pfizer used the incredible financial resources gained from selling its vaccine at high profit margins not only to do more research, but also to have a war chest try to win the social purpose marketing battle. Unfortunately, whilst it has succeeded in getting world-wide acceptance of the safety and efficacy of its vaccine, it has been most ineffective in getting its social purpose message (i.e., saving lives) across in low- and middle-income countries.

It does not help when, despite receiving public funding of over $8 billion, Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have steadfastly refused calls to urgently transfer vaccine technology and know-how to capable producers in low- and middle-income countries via the World Health Organisation (WHO). Although such a move could increase global supply, drive down prices and save millions of lives, Pfizer’ CEO, described the call to share vaccine recipes as “dangerous nonsense”.[xxvi]

Such messaging has caused many in society today to be distrustful of Big Pharma in general and of Pfizer in particular. This is because Pfizer’s vaccine has significantly boosted its bottom line to levels seen as obscenely profiteering from the suffering of others. When asked about this, Mr. Bourla said:

“I would say, can you think of someone that would deserve to make money other than someone who brought so much life saved, hospitalizations empty, economy, trillions going back to work — because we did just that. If you think that legitimate profit is perfectly fine, then you cannot find a more legitimate reasons to make money, than saving the world”.[xxvii]

The problem is that Pfizer did not save the whole world, only the rich world.

Today, the social purpose messages of the vaccine brands are fuzzy. With multiple safe and effective vaccines approved, parts of the globe are experiencing “brand tribalism”. Which brand of vaccine you want, or can get, has become a hot issue. In the United States, young vaccinators post their vaccine ‘team’ or ‘tribe’ preferences on social media, saying, “only hot people get the Pfizer Vaccine”. In Britain, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine invokes patriotism as well as warm feelings about its not-for-profit roots, even as some consumers prefer the ‘fancier’ Pfizer vaccine. In Hungary, fraught cold war politics have resurfaced as consumers can be vaccinated with one developed in the East or West. In Australia, since the move away from the AstraZeneca vaccine for people under 50 announced in April 2021, brand preferences became about safety rather than efficacy. Reports from elsewhere show younger and ineligible people are still stumping up to try and get vaccinated with whatever vaccine they can get.[xxviii]

Conclusion

There are many ways of using wealth to support personal values while effecting societal or environmental change.

Managers often have the best intentions when trying to link their brands with a social needs. However, choosing the right one can be difficult and risky and can have long-term implications. Competing on social purpose requires managers to create value for all stakeholders—customers, the company, shareholders, and society at large—merging strategic acts of generosity with the diligent pursuit of brand goals. The contrasting approaches of the vaccine manufacturers who answered the greatest social need in modern history but could not balance their marketing vs finance interface provides much food for thought for management accountants.

The opinions in this article reflect those of the author and not necessarily that of the organisation or its executive.

APPENDIX ONE

The Four Key Social Purpose Finance Strategies

- Responsible Investing (RI): This incorporates considerations related to environmental, social and governance goals (ESG) into portfolio management and investment decisions. People choosing to invest in RI mutual funds, or in a strategy designed around ESG considerations, seek positive performance and can feel confident that all potential risks and opportunities have been appropriately considered.

- Environmental Finance: These strategies seek to protect ecosystems by contributing to the economic growth of low-carbon power and other environmentally friendly industries and sectors. This can be anything from a bond that helps fund projects with clear environmental benefits, a mutual fund of eco-friendly companies or a direct investment in early-stage clean-technology companies. Environmental finance investors want to capture opportunities to protect the environment while diversifying their portfolios. Investments with an environmental finance goal may offer stable cash flows and are generally less volatile than — and not tied to — the performance of other assets.

- Development Finance: These offer investors who have a long-term view and an interest in emerging and developing markets around the world a way to geographically diversify their portfolios by helping to mobilise private-sector finance through lower-risk opportunities.

- Impact Investing: This is attractive to investors who seek to more intentionally effect positive social or environmental change and have a transformative social impact. While the strategies above feed the desire for a certain level of social or environmental change, such changes are generally secondary to the desire for competitive investment returns. In impact investing, such positive social or environmental change is not a secondary desire — it is equal to the desire for a satisfactory financial return. Rather than pursuing short-term gains, impact investors adopt a long-term strategy to bring about social change and public good.

References

[i] Sally Patten (2021), “Who Gives a Crap donates more than Qantas, CCA”, BOSS Magazine, Australian Financial Review, Feb 12. https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/leaders/who-gives-a-crap-donates-more-than-qantas-cca-20210208-p570jv#

[ii] Kotler, P., Roberto, N., & Lee, N. (2002), Social Marketing: Improving the Quality of Life (2nd Ed.), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA:

[iii] Jeff French & Ross Gordon (2015), Strategic Social Marketing. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

[iv] Saunders, S. G.; Barrington, D. J. & Sridharan, S. (2015), “Redefining Social Marketing: Beyond Behavioural Change“. Journal of Social Marketing, 5(2): 160–168.

[v] Kotler, P. & Lee, N. (2008). Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good (3rd Ed.)., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

[vi] Omar Rodríguez-Vilá and Sundar Bharadwaj (2017), “Competing on Social Purpose”, Harvard Business Review, 95:5, September–October, p. 94-101.

[vii] GSIA (2021) Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020, The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, Sydney, Australia.

[viii] Carl Hung (2021), “Three Reasons Why CSR And ESG Matter to Businesses”, Forbes, Sept 23. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2021/09/23/three-reasons-why-csr-and-esg-matter-to-businesses/

[ix] Neil Shenai (2018). Social Finance: Shadow Banking During the Global Financial Crisis. Springer International Publishing, New York, USA.

[x] Salway, Mark (2020-10-28). Demystifying Social Finance and Social Investment. Routledge. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom.

[xi] Baker, H. Kent; Nofsinger, John R. (2012-08-31). Socially Responsible Finance and Investing: Financial Institutions, Corporations, Investors, and Activists. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

[xii] Jed Emerson and Alex Nicholls, (2015), “Social Finance: Capitalizing Social Impact.” Social Finance, edited by Jed Emerson, et al., Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 1-45.

[xiii] Tom Espiner (2021), “AstraZeneca to take profits from Covid vaccine”, BBC News, 12 November, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-59256223

[xiv] Op. cit. GSIA (2021)

[xv] K.K. (2018), “What Is Sustainable Finance?”, The Economist, April 17. https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2018/04/17/what-is-sustainable-finance

[xvi] Op cit. Rodríguez-Vilá (2017)

[xvii] Eric Wargo (2011), “Beauty is in the Mind of the Beholder’ Journal of the Association of Psychological Science, April 1. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/beauty-is-in-the-mind-of-the-beholder

[xviii] Op cit. Rodríguez-Vilá (2017)

[xix] Paul Koku and Janek Ratnatunga (2013), “Green Marketing and Misleading Statements: The Case of Saab in Australia”, Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 11 (1): 1-8.

[xx] Op cit. Rodríguez-Vilá (2017)

[xxi] Op. cit. Espiner (2021).

[xxii] Michael Head (2022), “What happened to the AstraZeneca vaccine? Now rare in rich countries, it’s still saving lives around the world”, The Conversation, May 24. https://theconversation.com/what-happened-to-the-astrazeneca-vaccine-now-rare-in-rich-countries-its-still-saving-lives-around-the-world-181791

[xxiii] Kate Linebaugh (2022), “Pfizer’s CEO on Omicron, a Fourth Shot and 2022”, Podcasts, Wall Street Journal, January 10. https://www.wsj.com/podcasts/the-journal/pfizer-ceo-on-omicron-a-fourth-shot-and-2022/22b18590-5009-4d1b-9dee-7723ee91110c

[xxiv] Op. cit. Espiner (2021).

[xxv] Sarah Dransfield and Laura Rusu (2021), “Pfizer, Biontech and Moderna Making $1,000 Profit Every Second While World’s Poorest Countries Remain Largely Unvaccinated”, Oxfam, 16 Nov. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/pfizer-biontech-and-moderna-making-1000-profit-every-second-while-world-s-poorest

[xxvi] ibid

[xxvii] Op. cit. Linebaugh (2022)

[xxviii] Katie Attwell, et. al. (2021), “COVID Vaccination Has Turned into a ‘Battle Of The Brands: But Not Everyone’s Buying It”, The Conversation, June 21. https://theconversation.com/covid-vaccination-has-turned-into-a-battle-of-the-brands-but-not-everyones-buying-it-162181